Net Neutrality at the FCC: A Critique of the Legal Reasoning of its Net Neutrality Order

An earlier Davis Wright Tremaine advisory described the requirements of the Federal Communications Commission’s new “net neutrality” rules—transparency, no blocking, and no unreasonable discrimination. It also noted that the legal analysis in the Net Neutrality Order (NNO) “may stretch the FCC’s logic and authority beyond the breaking point.” This advisory expands on that observation. It also addresses the business, legal, and political context in which the rules were issued.

Net neutrality prior to the NNO

The rules are based on the FCC’s determination that regulation is necessary to assure the continued growth and development of the Internet. That is a departure from previous FCC administrations, for whom, with a few exceptions, “Hands off the Internet” was not just a slogan, but a policy.

Among those deregulatory programs, most relevant for present purposes are those classifying broadband Internet access as an “information service,” rather than a “telecommunications service.” The “classification orders” reflected the FCC’s view that broadband should be exempt from traditional common carrier / public utility regulation (e.g., the obligation to provide just, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory service upon request, transfer of control oversight, and possible regulation of rates, among others). The FCC viewed such regulation as a deterrent to broadband investment. (See this DWT advisory for analysis of the first of these orders, the 2002 Cable Modem Declaratory Ruling.)

The FCC found statutory authority for this deregulatory policy in, among other places, Section 230 of the Act, which states that the best way “to promote the continued development of the Internet” is to keep it “unfettered by Federal or State regulation.” Even the “infrastructure investment” promoting provisions of Section 706, which the FCC now cites as the basis for its net neutrality rules, were previously cited as authority for deregulatory programs.

While exempting broadband from common carriage requirements, the FCC sought to retain some authority over ISP conduct. In 2005, it issued its “Internet Policy Statement.” (See this DWT advisory.) The announced objective of the Policy Statement was the “encouragement of broadband deployment and the preservation and promotion of the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet.”

To achieve these goals, the Internet Policy Statement said that consumers were “entitled” to the following: (1) “access the lawful Internet content of their choice;” (2) “run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement;” (3) “connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network;” and (4) “competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.” The FCC cited various provisions of the Communications Act as authority for the Policy Statement, including Sections 230 and 706.

The Comcast-BitTorrent blocking case

Because the Internet Policy Statement was not a duly promulgated regulation based on a specific statutory grant of authority, many doubted whether it was actually enforceable. The first real test came a few years later when Comcast was found to be delaying the upload sessions of certain BitTorrent peer-to-peer file sharing applications.

At the time, BitTorrent use was a significant source of congestion on local broadband networks, particularly the shared local networks operated by cable providers. The problem was that certain popular “seed files”—the source of the mainly video content being downloaded by other users—would become engaged in continuous uploads. A few BitTorrent seeders in a neighborhood could significantly degrade the performance of the entire network.

To address this problem, engineers turned to an ingenious solution that monitored unusual upload activity. When certain thresholds were exceeded, instructions called “reset packets” were issued which disrupted the uploads. The extent, duration, and impact of these disruptions were disputed, but customers complained and net neutrality advocates Free Press and Public Knowledge initiated a formal proceeding at the FCC in November 2007.

The events that followed are well known. But less known is that the BitTorrent “problem” has lessened significantly, as broadband network capacities have increased, and the programming of the BitTorrent application has improved. But more important than both of those developments, BitTorrent file sharing is no longer the main way video content is accessed on the Internet. More people now use streaming video programs like Netflix and Hulu, which do not place the same strains on the upload capacity of local networks.

The FCC, however, did not wait for the Internet ecosystem to solve the BitTorrent problem by itself, and in August 2008 the agency issued its order sanctioning Comcast for blocking BitTorrent. (See DWT advisory.) The FCC ruled that Comcast had violated the Internet Policy Statement by “imped[ing] consumers’ ability to access the content and use the applications of their choice” (FCC Comcast Order ¶ 44). The FCC also found that Comcast “ha[d] several available options it could use to manage network traffic without discriminating” against peer-to-peer communications (id. ¶ 49).

The FCC claimed that the Policy Statement was enforceable pursuant to it its “ancillary authority” under Section 4(i) of the Act, which authorizes the FCC to “perform any and all acts, make such rules and regulations, and issue such orders … as may be necessary in the execution of its functions.” 47 U.S.C. § 154(i). The FCC’s Section 4(i) power is known as “ancillary authority” because, according to the courts, it authorizes the FCC to issue regulations that are “reasonably ancillary” to the effective performance of its statutorily mandated responsibilities.

On appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit rejected the FCC’s reasoning (as described in this DWT advisory). The court found that the agency had failed to link its order regulating Comcast’s provision of Internet access to any direct grant of statutory authority and that general statements of congressional policy—upon which the Internet Policy Statement relied—were insufficient to justify agency action. Comcast v. FCC, 600 F.3d 642, 658 (D.C. Cir. 2010).

Net neutrality in the aftermath of Comcast

The D.C. Circuit issued its Comcast order on April 6, 2010, a few weeks after the FCC published its National Broadband Plan, and just as the agency was preparing to deal with net neutrality. President Obama’s campaign platform included a net neutrality pledge (“Obama and Biden strongly support the principle of network neutrality to preserve the benefits of open competition on the Internet”), and FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski, a law school classmate of the President’s, a former FCC staff member, and an Internet entrepreneur in his own right, was appointed FCC Chairman doubtless in part with that pledge in mind.

While the Chairman was clearly committed to some kind of net neutrality order, prior to the court’s Comcast decision, most observers believed that the FCC would simply codify the Internet Policy Statement, perhaps with some enhancements, using the ancillary authority staked out in the agency’s Comcast order. The D.C. Circuit’s ruling complicated things, to say the least, and much of 2010 was dominated by the FCC’s attempt to respond.

Thus, although not expressly an order on remand, the NNO was drafted in the shadow of Comcast. The debate involved not just what rules would apply and to whom, but how the FCC would justify them. One approach would have been for the FCC to backtrack on its earlier orders and to reclassify broadband as a telecommunications service subject to Title II “common carrier” obligations. Others urged continued reliance on Title I, but for the FCC to better justify doing so.

In May 2010, the FCC announced its “third way” plan. Under the “third way,” the FCC would reclassify Internet transmission as a telecommunications service, but “forebear” from applying certain traditional common carrier obligations. Industry participants—in the form of a joint proposal from Google and Verizon—also floated proposals, as did members of Congress.

The main legislative effort—Rep. Henry Waxman’s bill—would have given the FCC direct authority to establish rules governing the terms and conditions of broadband Internet access service, while at the same time limiting the scope of what the FCC might do. The legislative effort lost steam after the November 2010 election, and for several weeks it looked like the net neutrality debate might lead nowhere.

It was from that turmoil that the NNO emerged. It claimed direct authority in Section 706 of the Act, as well as (apparently) ancillary authority tethered to various provisions from Title II and Title VI (common carrier and cable regulations, respectively).

The Net Neutrality Order

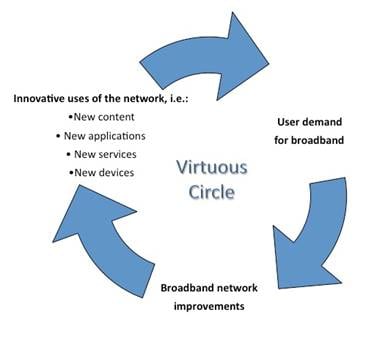

The avowed purpose of the NNO is to “preserve the Internet as an open platform” (¶ 1). The purpose of Section 706, on the other hand, is to “encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans” by authorizing regulators to “remove barriers to infrastructure investment.” The NNO links the one to the other through what it calls the “virtuous circle,” which it describes (in ¶ 14) as follows:

|

The Internet’s openness … enables a virtuous circle of innovation in which new uses of the network—including new content, applications, services, and devices—lead to increased end-user demand for broadband, which drives network improvements, which in turn lead to further innovative network uses. |

The lawyer/artist Bill Carleton graphically depicts this “virtuous circle” as follows:

Even those skeptical about government regulation promoting “virtue” will be hard pressed to disagree with the basic contours of this analysis. It appears self-evident that consumer demand for Internet content and applications drives demand for more robust networks, which has in turn, enabled new applications and new types of content. Nonetheless, the NNO concludes that past might not be prologue when it comes to broadband openness or infrastructure investment, and that regulatory intervention is necessary.

While the NNO cites only a handful of actual instances of questionable conduct by network providers (with those old warhorses, the Madison River-Vonage VoIP blocking and the Comcast-BitTorrent incidents, being most prominent), the NNO concludes that “broadband providers potentially face at least three types of incentives to reduce the current openness of the Internet.” NNO ¶ 21.

First, the FCC found that the changing nature of the Internet, with telephone and cable companies now the dominant ISPs, presents a new set of potentially anticompetitive incentives. “Edge providers over broadband increasingly offer actual or potential competitive alternatives to broadband providers’ own voice and video services, which generate substantial profits,” the order said (¶ 22). The order lists the challenge provided by VoIP providers and video aggregators, including Netflix, Hulu, YouTube, and iTunes. “By interfering with the transmission of third parties’ Internet-based services or raising the cost of online delivery for particular edge providers, telephone and cable companies can make those services less attractive to subscribers in comparison to their own offerings,” the FCC said (id.).

Second, it found that “broadband providers may have incentives to increase revenues by charging edge providers, who already pay for their own connections to the Internet, for access or prioritized access to end users” (¶ 24). In response to arguments that consumers can switch broadband providers if they are unhappy, the FCC found that “many end users may have limited choice among broadband providers” (¶ 27). The FCC rejected arguments that providers could use profits from prioritization to lower the cost of service based on the absence in the record of any broadband provider stating that it would use any revenue from edge provider charges to offset subscriber charges (¶ 28).

Third, the NNO found that charging edge providers for prioritized access will motivate broadband providers to “degrade or decline to increase the quality of the service they provide to non-prioritized traffic” (¶ 29). This could “increase the gap in quality (such as latency in transmission) between prioritized access and nonprioritized access, induce more edge providers to pay for prioritized access, and allow broadband providers to charge higher prices for prioritized access” (id.).

The FCC’s Section 706 analysis

The FCC admitted that the foregoing potential harms are speculative. But that alone does not doom the order to reversal by the courts. Regulators are typically allowed broad latitude when it comes to making predictive judgments about the industries they regulate. But for the FCC’s Section 706(a) justification to pass muster, it must demonstrate that the potential that broadband network operators might not continue to operate completely open networks constitutes a “barrier to infrastructure investment,” which net neutrality safeguards will “remove.”

The D.C. Circuit has suggested it might accept this linkage. For example, in a 2009 case, the court said, “[t]he general and generous phrasing of § 706 means that the FCC possesses significant, albeit not unfettered, authority and discretion to settle on the best regulatory or deregulatory approach to broadband.” Ad Hoc Telecomms. Users Comm. v. FCC, 572 F.3d 903, 906-07 (D.C. Cir. 2009). And in Comcast, the court said that Section 706 contains a “direct mandate,” implying that the statute is more than a general statement of policy. Comcast, 600 F.3d at 658.

In the FCC’s advocacy defending the Comcast order, however, the court found that the agency could not rely on Section 706 because of the agency’s earlier pronouncement (in the 1998 Advanced Services Order) that Section 706 “does not constitute an independent grant of authority.” The court found that the FCC’s 1998 view of Section 706 was still binding and could not be overruled “sub silentio.”

Thus, in the NNO, the FCC had to rehabilitate Section 706. Federal administrative agencies are, of course, free to depart from prior rulings, so long as they do so openly and provide a reasoned basis for doing so. That is what the FCC purported to do in the NNO (at ¶¶ 117-20). In his dissent, Commissioner Robert McDowell disagreed, asserting that “no language within Section 706—or anywhere else in the Act, for that matter—bestows the FCC with explicit authority to regulate Internet network management.”

If the NNO is appealed, that will be the main issue: whether Section 706 contains a congressional grant of authority to the FCC. The question was answered vaguely by the D.C. Circuit—some, “albeit not unfettered.” We review below some of the reasons why a court might be skeptical about the FCC’s reliance on Section 706.

First, notwithstanding the intuitive appeal of the “virtuous circle,” the FCC’s model does not appear to capture the crucial role that expected return on investment plays in sustaining the cycle. Broadband providers have invested in infrastructure for one reason—expected returns. And for 15+ years, those investments have been made without formal open network mandates. While the FCC’s policy judgment may be entitled to deference, the courts might not be so deferential when those judgments amount to second guessing broadband providers’ judgment about which business practices will maximize those returns, especially when the FCC specifically declined to conduct any market analysis.

Simply put: The NNO does not consider whether return on investment, the sine qua non of Section 706, and the investment in broadband infrastructure that such returns engender, might be maximized by factors other than network openness. A court might accept the FCC’s judgment that network neutrality rules further important social policies, but disagree that the record supports the determination that promoting “infrastructure investment” is one of them.

Second is the FCC’s assessment of the competition presented by other wireline and wireless providers. The NNO dismisses the potential market-disciplining effect of this competition, but the breeziness of its analysis is reminiscent of the FCC’s unbundling orders, which the D.C. Circuit characterized as “analytically insubstantial” for failing to adequately consider the presence of competitive alternatives or to “balance” the advantages of providing access with the cost of “spreading the disincentive to invest in innovation.” United States Telecom Association v. FCC, 290 F.3d 415, 427 (D.C. Cir. 2002). The NNO could be similarly criticized.

Third, “content is king.” While the FCC is concerned that network operators will one day charge content providers for access, the reverse possibility seems just as likely, if not more so. As demonstrated repeatedly by the retransmission battles between cable operators and the networks, and the negotiations for major sports’ rights, content providers frequently have the upper hand over distributors when it comes to carriage disputes.

Fourth is the nature of the “virtuous circle” itself, which is another way of describing the inherently interconnected nature of the Internet. As Bright House Networks explained in comments that DWT filed for the company in the FCC’s Open Internet Proceeding, no individual member of the Internet ecosystem—ISP or content provider—produces a finished service of value to end users. Instead, the value of the Internet arises from the joint production by the ecosystem as a whole. This creates a “commons”—a system in which members’ actions are governed not by short-term economic incentives, but, instead, by the internally generated obligations of the system itself. In such an environment, there is no reason to believe that an ISP would obstruct the ability of end-users to access the content. That would be self-defeating and degrade the value of the entire enterprise.

Finally, the breakneck speed of change on the Internet should make regulators wary about trying to predict its future. Three years ago, BitTorrent was one of the main ways that video content was accessed on the Internet. Today, Netflix and Hulu are far more popular. Two years ago, Google seemed poised to dominate navigation on the Internet, but just last month Facebook passed Google in terms of numbers of hits.

Indeed, some believe that Facebook is developing into a self-contained “walled garden,” like AOL used to operate in the early days of the Internet. AOL’s dominance was short lived. Facebook’s may be as well, but it is also possible that Facebook, not network operators or Internet search engines, could become the access choke points of the future. No one knows.

All of these considerations suggest that a reviewing court could be skeptical about the FCC’s determination of what is best for Internet infrastructure investment.

Other legal grounds cited by the FCC

The NNO (at ¶¶ 124-32) also relies on a hodgepodge of telecommunications and cable statutes, including §§ 201 and 251 (telecom) and §§ 628 and 616 (cable) to justify the new rules. (Commissioner Meredith Attwell Baker says in her dissent that the order relies “on 24 different claimed statutory bases.”)

The NNO’s legal analysis is problematic. For example, the NNO (at ¶¶ 125-26) asserts that the new rules are justified by the FCC’s authority over telecommunications carriers, explaining (1) that competition from over-the-top VoIP providers helps to ensure that telecommunications carriers’ rates are just and reasonable, and (2) that disruption of VoIP services would threaten that competition. The NNO therefore concludes (at ¶ 125) that, “[b]ecause the Commission may enlist market forces to fulfill its Section 201 responsibilities, we possess authority to prevent these anticompetitive practices through open Internet rules (id.).”

That conclusion is questionable. While the FCC has supervisory authority over the telecommunications services provided by telecommunications carriers, the NNO does not explain why it can directly apply a Title II statute to noncarriers. While the FCC is presumably invoking its ancillary authority, as Commissioner McDowell explains in his dissent, the NNO is far from clear or comprehensive on this point. (Commissioner McDowell’s dissent also provides a detailed explanation of why he thinks the NNO’s reliance on ancillary authority fails as a legal matter.) Similar analytical problems exist in the video and wireless sections.

Moreover, to the extent that the new rules are justified by the perceived need to protect the voice and video markets, the NNO clearly sweeps more broadly than necessary. Rules limited to preventing broadband providers from blocking or degrading third-party voice or video content would have been sufficient.

Conclusion

This analysis of the NNO should not be read as a policy critique of the importance of an open Internet. The question is whether intervention is necessary now and whether the FCC has adequately justified the specific intervention in the NNO.

While the NNO could be vulnerable to challenge as a legal matter, it is far from clear that anyone will actually do so. Some have suggested that the new rules largely maintain the status quo and the “virtuous circle” it has given rise to. Others, however, believe that the new requirements have profoundly changed economic incentives and increased regulatory uncertainty. And many are wary that the case-by-case enforcement process the rules envision will be burdensome, unpredictable, and lead to restrictions on broadband providers that the current rules do not contemplate.

While some public interest advocates believe the FCC should have gone further, they are unlikely to get more favorable rules in the near future. And the same thinking might govern broadband providers’ strategy. They would, of course, have preferred no rules at all, but the NNO is less intrusive than it might have been.

The new rules have not yet been published in the Federal Register, meaning that the appeal deadline is not for some time. We will keep you apprised of developments.