Rethinking Bank Leverage and Capital Requirements in 2025

On July 10, 2025, the federal banking agencies[1] published a proposed rule to change the enhanced supplementary leverage ratio (eSLR) for U.S. global systemically important bank holding companies (GSIBs) and their subsidiary banks, as well as total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) leverage buffer and long-term debt requirements (LTD) for U.S. GSIBs. The Fed will also host a July 2025 regulatory capital conference for an "integrated review" of the key pillars of the regulatory capital framework and seemingly welcome a broader range of perspectives for the future of capital framework reforms.

These developments come on the heels of the former Basel III endgame proposed capital rule, which was criticized by banks and consumer groups alike for gold-plating international standards and likely restricting U.S. consumers' access to credit. A complete rethink of the issue appears underway. And they are taking a different approach. In the current post-Chevron regulatory environment, as well as the deregulatory and pro-innovation policies of the current Administration, a more data-driven and consultative approach between industry and the regulators is unfolding.

We take a look here at the proposed rule's changes and other developments that bear on regulatory capital issues. Comments on the proposal are due August 26, 2025. Given the far-reaching consequences of this reevaluation of the U.S. approach to regulatory capital, banking organizations, foreign banks, non-banks seeking charters or to control banking organizations, and other interested parties should consider submitting comments.

Key Takeaways

- Backstop, not a binding constraint. The policy rationale for this proposal is to return the eSLR to being a backstop (a floor to prevent capital from falling too low), rather than a binding constraint (a limit that determines a banking organization's behavior).

- not risk-based—capital requirements are—the eSLR should only kick in when risk-based requirements are ineffective.

- When the eSLR becomes a binding constraint—even when a bank has enough risk-based capital—it can discourage banks from holding or intermediating low-risk assets like U.S. Treasuries or providing liquidity to financial markets.

- No significant capital changes proposed. The proposed rule wouldn't significantly change capital requirements for banking organizations or comprehensively change capital/leverage regulations. But it is intended to make certain activities with U.S. Treasuries more feasible for banking organizations—both at the holding company and subsidiary bank levels. The agencies also estimate that it will provide GSIBs "greater discretion to determine the optimal allocation of capital within the consolidated organization."

- Just the beginning. We expect the proposal to be the start of a broader review of regulatory capital and leverage requirements. Changes to these requirements would support the general deregulatory and pro-innovation policies of this Administration. For instance, stablecoins may be backed by U.S. Treasuries. The regulators likely are using a unified regulatory strategy, with this proposal as a first step and more proposed changes to follow. Regulators are likely to reconsider aligning capital requirements with actual risk and look for ways to eliminate redundancies.

- The agencies have asked for more information about other possible changes. Comments could discuss, for instance, the use of U.S. Treasuries in the denominators for various regulatory calculations, which would provide more substantial regulatory relief for banking organizations.

- Policy preference for U.S. Treasuries. Both the eSLR proposal and stablecoin legislation reflect a policy preference for U.S. Treasuries. Essentially, the proposal would support bank activities in the payment stablecoin space. The practical effect of banks having discretion to hold more U.S. Treasuries appears consistent with payment stablecoin legislation that would look to U.S. Treasuries (among other options) to back payments stablecoins, free from adverse effects on regulatory liquidity—and potentially—capital.

Click to enlarge and view 2-page chart

What the Proposed Rule Would Do

The proposal would modify the eSLR requirements for U.S. top-tier bank holding companies that are U.S. GSIBs and their subsidiary banks.

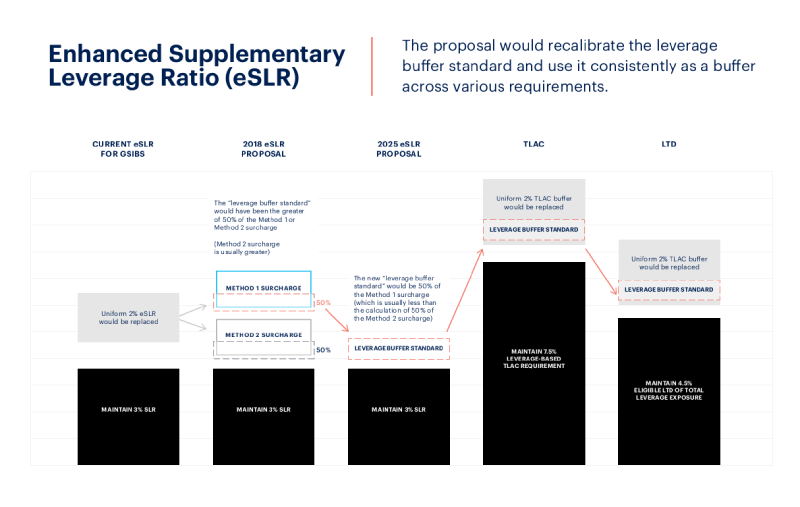

The proposal would modify the current (uniform) 2% eSLR leverage buffer that applies to U.S. GSIB.

- This eSLR leverage buffer is in addition to the supplemental leverage ratio (SLR) that requires banking organizations with more than $250 billion in total consolidated assets to maintain a ratio of tier 1 capital to total leverage exposure of at least 3%. Maintaining these buffers allows banking organizations to avoid limitations (e.g., on distributions and bonuses).

- Instead of the 2% uniform eSLR leverage buffer for U.S. GSIBs, the proposal would use 50% of the U.S. GSIB's risk-based capital surcharge calculated under Method 1 of the Federal Reserve's GSIB surcharge rule[2]—broadly similar to the approach under the international Basel III capital standards.

- This proposed change would provide greater capital relief compared to a 2018 proposal because the 2025 proposal would make the eSLR leverage buffer equal to 50% of only the Method 1 surcharge. The 2018 proposal would have looked at the overall risk-based capital surcharge—the greater of the surcharge calculated under Method 1 and Method 2, and Method 2 surcharges are typically higher than Method 1 surcharges.

The eSLR requirements also apply to banks that are subsidiaries of U.S. GSIBs (or Covered IDIs).

- Today, a Covered IDI must maintain an SLR of at least 6% to qualify as "well capitalized" under the prompt corrective action (PCA) regulations.

- Being "well capitalized," is a key factor in determining whether a bank holding company may qualify for financial holding company status to engage in expanded activities, streamlined application procedures, exemptions from brokered deposits regulations, among other considerations. Being "well managed" is a key factor too, which the Fed is also rethinking.

- The proposal would basically align the eSLR standard for the U.S. GSIB holding company and its subsidiary bank by replacing the current 6% "well-capitalized" threshold from the PCA framework with an eSLR buffer standard equal to 50% of the risk-based GSIB surcharge applicable to the depository institution's U.S. GSIB holding company calculated under Method 1 (the same calculation as above).

TLAC and LTD Proposed Changes

The proposed rule would also modify the Fed's total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) leverage buffer and leverage-based long-term debt (LTD) requirements for U.S. GSIBs.

Leverage-based capital buffer

- Today, the TLAC rule requires a U.S. GSIB to maintain a buffer of at least 2% of its total leverage exposure (the denominator for the SLR and eSLR), and it must comply with the minimum 7.5% leverage-based TLAC requirement. Breaching the buffer also restricts the U.S. GSIB's ability to make distributions and pay bonuses.

- Similar to the proposed revisions to the eSLR, the proposal would replace the uniform 2% buffer with a buffer equal to 50% of the U.S. GSIB's risk-based GSIB surcharge as calculated under Method 1 (the same calculation as above).

Long-term debt (LTD) requirements

- Today, U.S. GSIBs must maintain eligible LTD of 4.5% of total leverage exposure.

- Consistent with the eSLR modifications, the proposal would modify the leverage-based LTD requirement for U.S. GSIBs to 2.5% plus 50% of the U.S. GSIB's risk-based GSIB surcharge as calculated under Method 1 (the same calculation as above).

What the Proposed Rule Would Not Do

- Like the 2018 proposal, the 2025 proposal would not exclude U.S. Treasuries or deposits at Federal Reserve Banks from the denominator of the eSLR calculation. But the Fed has requested comments on this potential change.

- If adopted, this change would result in better regulatory ratios without raising capital requirements.

- In 2020, in response to volatility and associated market strain during the pandemic, interim final rules temporarily excluded on-balance sheet U.S. Treasury securities and deposits at Federal Reserve Banks from total leverage exposure. This regulatory relief expired on March 31, 2021.

- The proposal explains that although "the capital requirements of the depository institution subsidiaries of GSIBs would decline, capital requirements applicable to GSIBs would remain approximately at their present level." This is because risk-based capital requirements are higher at the GSIB level: the stress capital buffer and GSIB surcharge requirements apply at the holding company level, not to subsidiary banks.

- The regulators also explain that "GSIBs would not be able to significantly increase dividend payments or other capital distributions, due to bank holding company capital requirements."

Comments Requested

Although not substantively proposed, the regulators have ask for comments on the following, which could expand the regulatory relief in a final rule or follow-on developments:

- Potential changes to the calculation of the denominator of both the SLR and eSLR to exclude U.S. Treasury securities that are reported as trading assets on a bank holding company's consolidated balance sheet and that are held at a broker-dealer subsidiary (or foreign equivalent) that is not a subsidiary of a depository institution.

- Other changes to consider "for purposes of ensuring that the eSLR buffer standard generally does not serve as the binding capital constraint for GSIBs." Besides generally recalibrating the eSLR buffer requirement through the nominal percentages used in regulation, we anticipate technical comments ranging from market and risk sensitivity to repurchase agreements ("repos") and derivative exposures based on data-rich analyses.

- Other regulatory capital changes "to address the binding nature of the supplementary leverage ratio requirements relative to risk-based capital requirements, consistent with safety and soundness."

- "[A]lternative methods of targeting exclusions from the supplementary leverage ratio," including those "based on specific activities such as Treasury-based repurchase or reverse repurchase arrangements."

- Additional changes to consider "in the context of the mandatory central clearing of certain U.S. Treasury transactions," including how repo-style transactions may "be more appropriately reflected in the supplementary leverage capital requirements or other areas of the regulatory framework."

Stress Tests

In addition, the overall case for capital changes and relief was boosted by the recent positive stress test (DFAST) results announced by the Fed on June 27, 2025, which considers whether banks are sufficiently capitalized to absorb losses during a severe recession. The results indicated that all banks tested remained above their minimum common equity tier 1 (CET1) capital requirements during the stress scenario, confirming the positive efforts of banks and regulators over the last 17 years since the Global Financial Crisis.

Despite the good news with respect to capital, various industry advocates have pointed out that volatility in the results remains, leading to renewed requests that the Fed further modify its models and make them more public so that there can be more stability in results and more predictability for bank capital planning.

In many ways, this is a logical result of a decade and a half of stress tests and the continual demands for more transparency from the federal banking regulators. Industry argues that additional transparency into the tests does not affect adequate levels of bank capital and liquidity. It appears that the Fed may be moving toward that view. This change is consistent with renewed calls to respect regulatory tailoring and for supervisory reform.

Concluding Thoughts

Taken together, these efforts to make capital and leverage requirements more efficient should be evaluated along with the advent of tools that make liquidity management more transparent, predictable, and efficient. If managed appropriately, this should enable banks to free up idle capital from their balance sheets to drive further lending and support the economy in general.

From a larger perspective, the proposal can be seen as part of the overall transformation of U.S. financial institutions through modernization, including open banking, fintech models, new charters, blockchain and crypto tools, and the globalization and disintermediation of payment systems. The trend is unlikely to subside.

+++

DWT's banking and payments practice is a multidisciplinary team of subject matter experts in financial services, privacy, data security, technology transactions, enforcement and litigation, and other relevant areas. The B&P team regularly advises financial institutions on compliance with applicable federal and state banking laws and related requirements.

For more information or assistance in preparing a comment letter to the proposed rulemaking, please contact any of the authors or your usual DWT contact.

[1] The Federal Reserve Board (Fed), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

[2] The Fed's capital rule requires a GSIB to calculate its GSIB risk-based surcharge in two ways: Method 1 and Method 2. The GSIB must apply the higher of the two results for its surcharge. Method 1 is based on five categories that are correlated with systemic importance—size, interconnectedness, cross-jurisdictional activity, substitutability, and complexity. Method 2 uses similar inputs but replaces substitutability with the use of short-term wholesale funding and is calibrated in a manner that generally will result in surcharge levels for GSIBs that are higher than those calculated under Method 1.