Here's the Deal: Could the Social Cost of Carbon Become a Key Component of Biden's Climate Strategy?

Under President Biden, the federal government will dramatically alter the way it calculates the social cost of greenhouse gases (GHGs). In his first day in office, President Biden issued an Executive Order re-establishing the Interagency Work Group on Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases (IWG) and ordering the IWG to publish interim values for the social cost of carbon (SCC), social cost of nitrous oxide (SCN), and social cost of methane (SCM) within 30 days.

In February 2021, the newly reconstituted IWG issued its interim estimates and technical support document. The IWG concluded that the social cost of GHG values used under the Trump Administration "fail to reflect the full impact of GHG emissions."

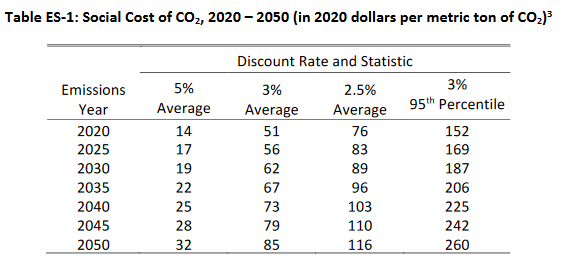

The IWG restored the SCC, SCN, and SCM values to those published in August 2016 (reported in 2020 dollars but otherwise identical). For comparison, the Trump Administration valued the SCC in 2020 at around $1 to $7 per metric ton of CO2, whereas the restored IWG values put the SCC in 2020 at $14 to $152.

The IWG was further tasked with conducting a thorough analysis of how high the social cost of GHG values should be adjusted moving forward. The IWG will publish new estimates in January 2022. Given the emerging science indicating greater harm than was previously understood, the IWG's social cost values may rise significantly.

These interim values and the updated values forthcoming in 2022 will be incorporated into a broad array of actions by the federal government, including procurement, the development and application of environmental laws and regulations by federal agencies, and President Biden's ambitious infrastructure plans.

What Is the Social Cost of Carbon?

Simply put, the SCC monetizes damages associated with each additional ton of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere as a result of a project's construction or operation. For example, if the SCC is valued at $50 per metric ton and a proposed project is estimated to emit one million tons of CO2, then the project's SCC would be $50 million.

However, the difficulty comes with determining what SCC value to apply. The IWG SCC estimates are not a single number but, instead, a range of four estimates based on different discount rates.

Discount rates allow economists to measure the value of money over time—the tradeoff between what a dollar is worth today and what a dollar would be worth in the future. The four IWG SCC values reflect the average cost across models and socioeconomic emissions scenarios based on three discount rates (2.5 percent, 3 percent, and 5 percent), plus a 95th percentile estimate that represents catastrophic, low-probability outcomes.

The IWG SCC estimates for the years 2020 through 2050 are as follows:

Social Cost of CO2 2020-2050 (in 2020 dollars per metric ton of CO2)

So, which SCC value do you choose? The IWG recommends using a 3 percent discount rate (valued at $51 per metric ton of CO2 in 2020). However, different agencies—and different states—select different discount rates for their analyses. Frequently, agencies will conduct their economic analyses using a range of SCC values.

When reviewing proposed projects, agencies are often required to consider certain factors and conduct a cost-benefit analysis. Thus, increases in SCC could have far-reaching impacts on the outcome of federal decision making. Below we review three areas in which that is likely to be the case.

Implications for NEPA Analysis

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) applies to any "major federal action" that affects the "human environment," including regulatory approvals by all federal agencies. Each agency has its own NEPA rules, in addition to those promulgated by the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ).

Typically, the agency will prepare an Environmental Assessment (EA) determining whether a federal action has the potential to cause significant environmental effects. If the federal action does have a potential to cause significant environmental effects, an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) will be prepared. Through that process, the agency must consider reasonable alternatives to the proposed action.

Increasing the SCC could affect the NEPA review process in at least two ways. First, it could result in more proposed actions requiring an EIS because a high SCC would imply potentially significant environmental effects. Second, it could affect how "reasonable alternatives" are being considered, giving more weight to alternatives with a lower SCC.

Although it is well-established that the NEPA review process must generally consider the effects of GHG emissions, courts have typically deferred to agencies as to whether and how to utilize the SCC. That deference will give the Biden Administration considerable leeway to apply the SCC across a broad range of decisions without a significant risk of judicial interference.

Potential Implications for FERC Review

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has a new chairman, Richard Glick, who has made clear that his vision for FERC includes making climate change a key consideration when reviewing projects. In March 2021, FERC assessed for the first time a proposed natural gas pipeline's GHG emissions and their contribution to climate change but concluded that the pipeline should nevertheless be approved.

Chairman Glick explained that "[g]oing forward, we are committed to treating greenhouse gas emissions and their contribution to climate change the same as all other environmental impacts we consider." In doing so, the Commission reversed its prior conclusion that it was "unable to assess the significance of a project's GHG emissions or those emissions' contribution to climate change."

Part of FERC's review is to determine whether a project is "required by the public convenience and necessity." In an article published in 2019, Chairman Glick also concluded that "[t]he Commission's ultimate responsibility is to protect the 'public interest.' There is perhaps no greater concern to the public interest than the existential threat posed by anthropogenic climate change." Accordingly, it seems only a matter of time before FERC's consideration of the SCC leads to the denial of a project.

State-Level Implications

A growing number of states have incorporated the SCC into a variety of statutes, regulations, policies, and programs. For example, the SCC is now evaluated in the context of:

- Utility-integrated resource planning (e.g., Colorado, Nevada, Washington);

- The evaluation of proposals for new power plants (e.g., Colorado, Nevada, Minnesota, Maine);

- The valuation of integrated distributed energy resources (e.g., California);

- The provision of incentives for facilities generating low-carbon electricity (e.g., Illinois, New York);

- The setting of compensation for owners of solar panels that supply surplus power to the grid (e.g., Minnesota, New York);

Most of these states have adopted the IWG SCC values. So the likely increases in those values by the IWG—starting next year—will almost certainly be followed by increases in those values utilized by state governments. And if the projected magnitude of harm due to climate change continues to grow, the upward trend in SCC values can be expected to follow for decades to come.